Everyone talks about strategy, but what is it

Truth be told, strategy is one of the most overused buzzwords in the real world, to make things sound relevant and important. Are you sometimes frustrated by occasions that treat strategy like the snake oil to anything from a product design doc to annual planning? I feel the pain here.

To feed my growing curiosity, I spent the first half of January reading and jotting down notes from this book - Understanding Michael Porter: The Essential Guide to Competition and Strategy by Joan Magretta, just to get a proper intro on this heavily discussed topic in both academia and the business world.

I’m by no means an expert in strategy by reading one book. However, I do like to share my learning here, as this is the very first book that clearly lays out the dynamics of competition and the role strategy plays in business context.

TL;DR 😛

- Strategy explains how an organisation, faced with competition, will achieve superior performance

- The key to competitive success – for businesses and non-profits alike – lies in its ability to create unique value

- Competition is not a zero-sum game (i.e. to be the best), but to be unique

Competitions#

The book starts with Porter’s take on competition. Should there be no competition, there’d be no need for strategy.

It’s a misconception that competition means defeating all your rivals and being the top in the industry. This is coined by Michael Porter as competition to be the best, and to him, is absolutely the wrong way to think about it.

“The real point of competition is not to beat your rivals. It’s to earn profits”

Different from sports or warfare, where there is only one to win, business competition is much more complex, open-ended and multidimensional. Take smartphone industry as an example, there are a handful of brands out there like Apple, Google, Samsung, Huawei, Xiaomi, etc with different degrees of differentiation from operating systems, cameras, user interface to designs and pricing. They are essentially competing to meet different layers of consumer needs instead of dominating the entire market.

According to Michael Porter, strategic competition means choosing a path different from that of others. This concept is all about uniqueness in value creation and how you are creating it.

Now you might wonder why some companies are more profitable than others? In the book, this big question can be answered by the following framework –

- the structure of the industry (i.e. the five forces)

- a company’s relative position within an industry (i.e. competitive advantage)

The Five Forces#

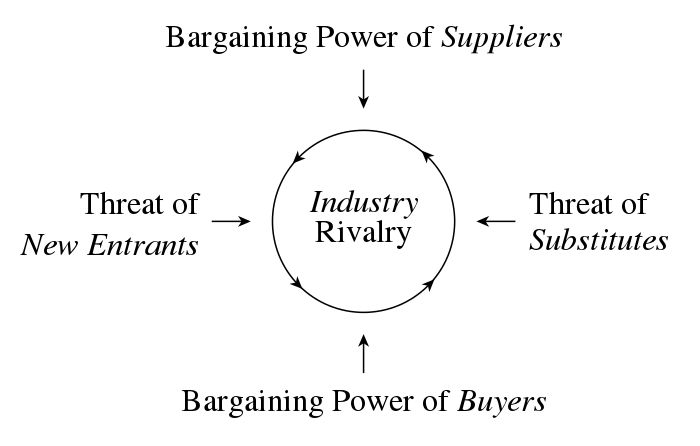

Below is a classic chart of the five forces that you might have encountered in Economics 101.

Porter has found the following links between industry structure and profitability:

- Although industries might appear different on surface, the same forces work under skin

- Industry structure determines profitability, not whether the industry is high growth or low, high tech or low

- Industry structure is sticky

- There are limited number of structural forces at work in every industry that systematically impact profitability in a predictable direction

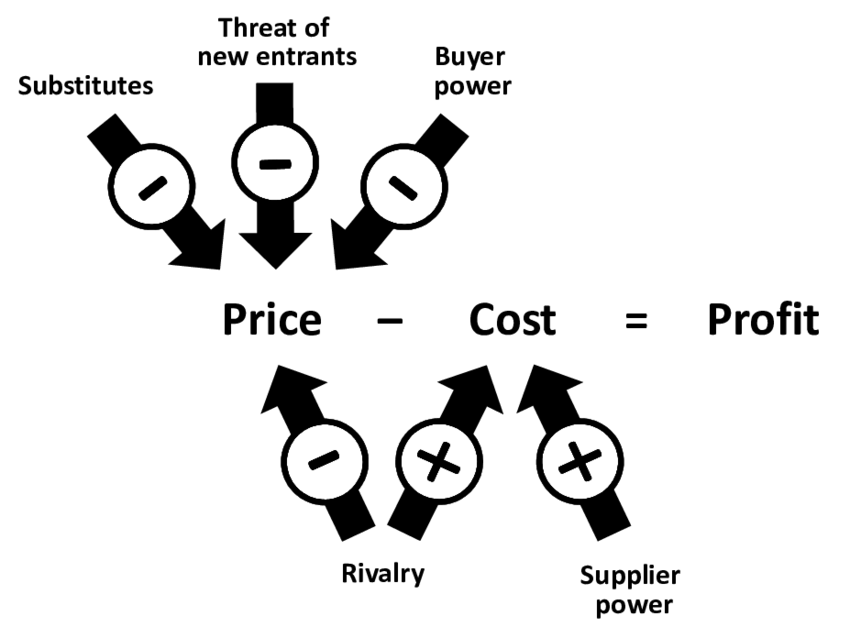

- ☝️General rule: the more powerful the force, the more pressure it will put on prices or costs or both (see below)

Buyers#

“Powerful buyers will force prices down or demand more value in the product, thus capturing more of the value for themselves”

When assessing buyer power, the channel through which products are delivered can be as important as the end users. This is especially true when the channel influences the purchase decisions of the end-user customers. Both industrial customers and consumers tend to be more price sensitive when what they’re buying is:

- Undifferentiated

- Expensive relative to their other costs or income

- Inconsequential to their own performance

Suppliers#

“Powerful suppliers will charge higher prices or insist on more favourable terms, lowering industry profitability”

When analysing the power of suppliers, be sure to include all of the purchased inputs that go into a product or service, including labour. Forces of buyers and suppliers are considered powerful if:

- They are large and concentrated relative to a fragmented industry

- The industry needs them more than they need the industry

- Switching costs work in their favour

- Differentiation works in their favour

- They can credibly threaten to vertically integrate into producing the industry’s product itself

Substitutes#

“Products or services that meet the same basic need as the industry’s product in a different way - put a cap on industry profitability”

The following questions help to assess the threat of substitute:

- Look to the economics, specifically to whether the substitute offers an attractive price-performance trade-off relative to the industry’s product

- The sweet spot isn’t always lower-priced alternative, e.g. the Madrid - Barcelona high-speed train is a higher-value, higher-price substitute to flights

- Switching costs play a significant role in substitution

New Entrants#

“Entry barriers protect an industry from new comers who would add new capacity”

To assess the barrier of entry:

- Do producing in larger volumes translate into lower unit costs?

- If there are economies of scale, at what volumes do they kick in?

- Where do these economies come from: spreading fixed costs over larger volume? more efficient technologies that are scale dependent? increased bargaining power?

- Will customers incur any switching costs in moving from one supplier to another?

- Does the value to customers increase as more customers use a company’s product (i.e. network effect)

- What’s the price of admission for a company to enter the business - how large are the capital investments and who might be willing and able to make them?

- Do incumbents have advantages independent of size that new entrants can’t access? (e.g. proprietary technology, well-established brands, prime locations and access to distribution channels)

- Does government policy restrict or prevent new entrants

- What kind of retaliation should a potential entrant expect should it choose to enter the industry

Rivalry#

“If rivalry is intense, companies compete away the value they create passing it on to buyers in lower prices or dissipating it in higher costs of competing”

Rivalry can take a variety of forms: price competition, advertising, new product intros and increased customer service. For Porter, price competition is the most damaging form of rivalry.

To assess rivalry:

- If the industry is composed of many competitors or if the competitors are roughly equal in size and power

- Slow growth provokes battles over market share

- High exit barriers prevent companies from leaving the industry

- Rivals are irrationally committed to the business; that is, financial performance is not the overriding goal

Understanding these five forces helps both existing business owners and aspiring entrepreneurs to synthesise the industry analysis and how they can create unique values. Below are the typical steps for industry analysis:

- Define the relevant industry by both its product scope and geographic scope. The rule of thumb is where there are differences in more than one force, or where differences in any one force are large, you are likely dealing with distinct industries

- Identify the players constituting each of the five forces and, where appropriate, segment them into groups

- Assess the underlying drivers of each force - which one is strong and which is weak

- Step back and assess the overall industry structure. Think about which forces control profitability and then dig deeper into the most important forces in the industry

- Analyse recent and likely future changes for each force - how are they trending and how might competitors or new entrants influence industry structure

- How can you position yourself in relation to the five forces

Ultimately, strategy can be viewed as building defences against the competitive forces or finding a position in the industry where the forces are the weakest.

Competitive Advantage#

“A difference in relative price or costs that arises because of differences in the activities being performed”

Similar to Porter’s definition of competition, competitive advantage is not about trouncing rivals, but about creating superior value, by which he refers to relative pricing and cost.

Higher pricing can only be sustained by offering unique values. Through generating more buyer value, a company can raise buyer’s willingness to pay, the mechanism that makes it possible to charge a higher price relative to rival offerings. In industrial markets, buyer value can usually be quantified and described in economic terms, such as cost saving of a product relative to labour costs. With consumers, buyer value is more emotional or intangible (e.g. organic foods, farm-to-table egg, brand values etc.).

Ability to produce at lower cost than rivals might come from lower operating costs, or from using capital more efficiently, or a combination of both.

“Competitive advantage arises from the activities in a company’s value chain”

According to Porter, all costs or price differences between rivals arise from the hundreds of activities that companies perform as they compete, which is the value chain.

Here, activities and activity system mean discrete economic functions or processes, such as managing a supply chain, operating a sales force, developing products, or delivering them to the customer. An activity is usually a mix of people, tech, fixed assets, sometimes working capital and various types of information.

It’s extremely useful to disaggregate a company into its strategically relevant activities in order to focus on the sources of competitive advantage, that is, the specific activities that result in higher prices or lower costs.

The book lays out the following steps to approach value chain analysis:

- Laying out the industry value chain, i.e. its prevailing business model and the way it creates value; most companies in the industry have chosen “to sit” in relation to the larger value system

- Compare your value chain to the industry’s - the goal here is to capture every step in the value-creating process; if your value chain looks like everyone else’s, then you’re engaged in competition to be the best

- Zero in on price drivers as those activities have a high current or potential impact on differentiation

- Zero in cost drivers by paying special attention to activities that represent a large or growing percentage of costs

Strategy#

Competition and strategy go hand in hand. In Porter’s definition, strategy is normative rather than descriptive. Here I summarise the framework in the book to distinguish a good strategy from a bad one:

- A distinctive value proposition

- A tailored value chain

- Trade-offs different from rivals

- Fit across value chain

- Continuity over time

A distinctive value proposition#

Value proposition answers the following three fundamental questions:

Which customers to serve?

- Within an industry, there are usually distinct groups of customers, or customer segments. A value proposition can be aimed specifically at serving one or more of these segments

- That choice then leads directly to the other two legs of the triangle: needs and relative price

- Essentially, it’s about finding a unique way to serve your chosen segments profitably

Which needs to meet? (products, features, services)

- Typically, value proposition based on needs appeal to a mix of customers who might defy traditional demographic segmentation

What relative price will provide acceptable value for customers and acceptable profitability for the company (premium, discount)

- Some value propositions target customers who are overserved (and hence overpriced) by other offerings in the industry. A company can win these customers by eliminating unnecessary costs and meeting “just enough” of their needs

- Where customers are overserved, the lower relative price is often dominant leg of the triangle

- Similarly, value propositions target customers who are underserved (and hence underpriced). The unmet need is typically the dominant leg of the triangle, while the higher relative price supports the extra costs the company has to incur to meet it

- If you are trying to serve the same customers and meet the same needs and sell at the same relative price, then by Porter’s definition, you don’t have a strategy

A tailored value chain#

The essence of strategy and competitive advantage lies in the activities, in choosing to perform activities differently or to perform different activities from those rivals.

A set of generic strategies: focus, differentiation, and cost leadership

- Focus refers to the breadth or narrowness of the customers and needs a company serves

- Differentiation allows a company to command a premium price

- Cost leadership allows it to compete by offering a low relative price

Trade-offs different from rivals#

- Trade-offs are the strategic equivalent of a fork in the road. If you take one path, you cannot simultaneously take another

- Building and sustaining competitive advantage means that you must be disciplined about saying no to a host of initiatives that would blur your uniqueness

- The notion that customer is always right is one of those half-truths that can lead to mediocre performance (because some of those customers are not your customers)

Fit across value chain#

- Fit has to do with how the activities in the value chain relate to one another. Good strategies depend on the connection among many things

- The first kind of fit is basic consistency, where each activity is aligned with the company’s value proposition and each contributes incrementally to its dominant themes

- The second type of fit occurs when activities complement or reinforce each other

- Substitution, i.e. performing one activity makes it possible to eliminate another

Continuity#

- Continuity reinforces a company’s identity - it builds a company’s brand, its reputation and its customer relationships

- Continuity helps suppliers, channels and other outside parties to contribute to a company’s competitive advantage

- Continuity fosters improvements in individual activities and fit across activities; it allows an organisation to build unique capabilities and skills tailored to its strategy

However, a strategy needs to change if:

- First, as customer needs change, a company’s core value proposition may simply become obsolete

- Second, innovation of all sorts can serve to invalidate the essential trade-offs on which a strategy relies

- Third, a technological or managerial breakthrough can completely trump a company’s existing value proposition

I hope this post serves a good intro to understanding strategy, and some of the concepts and frameworks here can be applied to analysing businesses! If you have any thoughts or articles to share, please drop me a line 🙌.